Thursday, October 30, 2008

plan-séquence en animation

Wednesday, October 29, 2008

Re-visiting Tarkovsky

Nier le concret

« La passion devient l’élément essentiel de ce cinéma parce que, à l’inverse de l’action, elle noue des narrations falsifiantes à des descriptions pures » (Deleuze, p.177).

Cette phrase de Deleuze énonce un paradoxe cinématographique: comment tromper le concret d’une image? D’un coté, l’image est concrète, elle est ce qu’elle est. Nous voyons des couleurs, des formes, des mouvements, de l’espace, le temps passer, etc. En ce sens, le cinéma est très fréquemment constitué de descriptions pures. Par contre, cette image visuelle n’est pas uniquement ce qui forme l’image cinématographique. La narration (autant le développement de l’histoire que la voix off) peut confronter ces images, nier le concret, ce que l’on voit. Je crois que c’est ce que Resnais et Robbe-Grillet ont réussit à accomplir avec le film. Nous voyons des descriptions pures après d’autres descriptions pures et chacune nie la précédente. Dans chaque plan, il y a de l’addition et/ou de la soustraction qui change le souvenir d’une image. Cette image, qui est vraie parce qu’elle est elle-même, devient alors fausse dans un contexte narratif. Toutefois, je crois que ce qui est exprimé dans le film de Resnais n’est pas unique à ce film, mais bien une exagération de ce qui se trouve dans la grande majorité des films (avec l’apport du montage, etc.). C’est peut-être aussi contre cela que Tarkovski se rebelle dans Le temps scellé, lorsqu’il veut retrouver la vérité de l’image ou lorsqu’il privilégie le plan-séquence au montage.

Tuesday, October 28, 2008

Still Orang-Outans

Mais concordent-ils vraiment?

Lorsqu'il m'arrive de réfléchir à la temporalité au cinéma, il est automatique pour moi de penser au plan-séquence. Pourquoi en est-ce ainsi? J'imagine que pour moi, c'est dans ces moments si fluides que le temps devient important, que j'y prête alors une grande attention. Le concept du plan-séquence au cinéma m'obsède, je vais donc essayer d'y dédier mes prochaines posts, étant en retard de quelques-unes.

Monday, October 27, 2008

Le Souvenir des illusions

C’est ce type de narration qui constitue L’Année Dernière à Marienbad d’Alain Resnais. Les deux principaux personnages de ce film s’y contredisent, l’un mentionnant des souvenirs de moments vécus à Marienbad l’année précédente, l’autre affirmant n’avoir aucune réminiscence de ces instants. Chaque personnage devient faussaire et jamais la narration ne permet au spectateur de déceler la vérité. Les images de souvenirs sont introduites par le personnage masculin, puis reniées par la femme. Les contradictions s’affichant à l’intérieur de chaque image telles que les ombres infidèles soulignent l’impossibilité des souvenirs décrits et la défaillance de la mémoire de chaque personnage, mais suggèrent aussi l’irréalité de leur présent. Le film parvient à reconstituer un amas de souvenirs falsifiés par la mémoire, proposant par le fait même que la vérité s’est effacée avec le temps et qu’elle ne pourra jamais être vécue à nouveau. Les défauts de la mémoire trahissent chaque personnage en lui-même.

Deleuze mentionne également que « la passion devient l’élément essentiel de ce cinéma parce que, à l’inverse de l’action, elle noue des narrations falsifiantes à des descriptions pures » (Deleuze, p.177). Dans L’Année Dernière à Marienbad, les personnages sont animés par un désir de faire resurgir une passion éteinte, qu’elle soit véritable ou qu’elle n’ait été que rêvée. Ils ont le désir de ramener à la surface des souvenirs purs, mais l’inconstance de leur mémoire les retient de se faire confiance à eux-mêmes et empêche le spectateur de déceler toute forme de vérité.

Saturday, October 25, 2008

digital>analog>digital>analog>digital...ad infinitum

The thrust of the process is not to become the equivalent of the "model" but to turn against it and its world in order to open up a new space for the simulacrum's own mad proliferation. The simulacrum affirms its own difference. (ibid.)

Friday, October 24, 2008

The Digital Passion of Resolution

Deleuze's Cinema 1 & 2

You can download a zipped file of Deleuze's Cinema 1 & 2 at the following link.

Simply click on the link and press on the button that says download.

Enjoy,

Felix

https://www.yousendit.com/download/Y2o5UXVqVEhiR0kwTVE9PQ

Fabulation

Deleuze réussit ici encore une fois à briser une dichotomie facile, celle entre cinéma de fiction et cinéma documentaire, une séparation dont tout le monde reconnaît les apories et problèmes fondamentaux mais qui est quand même persistante et dont il est difficile de se défaire complètement. Le cinéma de Perrault, dont on a si souvent dit qu’il était un cinéma du réel, devient ainsi sous la plume de Deleuze un cinéma de fabulation; un des grands maîtres du documentaire devient l’artisan exemplaire portant les puissances du faux au cœur du récit cinématographique. Pour la suite du monde : Nietzsche aurait probablement dit pour la suite de la vie. Ce film nous offre bel et bien, non pas un regard nostalgique sur des fragments d’une réalité en voie de disparition, mais une véritable ode sur le pouvoir de fabulation et de création qui peut jaillir de la parole et de l’action de gens simples. Nietzsche n’aurait peut-être pas cherché, ni espéré trouver, son surhomme à l’Ile-Aux-Coudres, mais je ne peux m’empêcher de voir en Alexis un de ces généreux personnages, un «bon [qui] se laisse épuiser par la vie plutôt qu’il ne l’épuise, se mettant toujours au service de ce qui renaît de la vie, de ce qui métamorphose et crée.» (Deleuze, 185)

Thursday, October 23, 2008

An experiment with time

This simple experiment allows anyone with patience to experience how objective time can be momentarily replaced with subjective time.

You will need a clock with a second hand to try this for yourselves.

1/ Place the clock on a table in front of you so you can clearly see the second moving without any effort, through half closed eyes.

2/ Look at the clock and follow the movement and rhythm of the second hand in a thoughtful way. Continue this until you feel completely absorbed by this movement.

3/ Close your eyes and visualize yourself in a place you are familiar with and would like to be.

Fill this visualization with as much sensation as possible.

A good example would be lying on a familiar beach, the sun warming your skin, the sand soft beneath your back, the sound of the tide lapping the shore in the background.

4/ When you feel that you are fully immersed in this visualization, fully relaxed, slowly open your eyes halfway. Don't focus. Just let your eyes find the clock that you had placed on the table in front of you.

- This is the point where the second hand on the clock will appear to stick or hover. If you are used to meditating, you can see the second hand stop completely, especially during that instant before you break out of this semi-meditative state.

Paraphrased from

Stalking the Wild Pendulum by Itzhak Bentov. pages 60-61

If we were to ask the brain how it would like to be treated, whether shaken at a random, irregular rate, or in a rhythmic, harmonious fashion, we can be sure that the brain, or for that matter the whole body, would prefer the latter. -Bentov

Silent train...

Wednesday, October 22, 2008

The Powers of the False and Malkovich

Voir ce qu'on entends

I hear what my hand is seeing....

I'm a true believer that the way we use (or not) our senses (see, ear, touch, smell and taste) changes the way we react (physically, emotionally and philosophically) toward arts. A film like we saw last week, even if it is made to create a unison between visual and audio, don't mean it is the only way that it could take form. In fact, seen this film without the sound (or just hearing the sound without seeing the images) could bring out something else that what happened on screen before. Cinema is a particular medium because it work with the visual and the auditory, but we often give more importance to the visual. What we hear pass in us in a more subtle way than what we see. The human brain is mostly functioning like that.

If you think of other kind of art, you will naturally tend to separate them between the visual and the auditory category, but they are not just limited to one. When you react with one sense, you just don't acknowledge the participation of the others on a conscious level. But without knowing it, the sensation that you feels will each time require the involvement of more than one sense. When you perceive the sensation brought to you by an experience (film, art, emotion, moment, etc), if you try to consciously acknowledge how each of your senses reacts, you will feel each one separately and together in the same time. At this moment, you will experience more than what you can imagine possible -- you'll know the perception that each brings out, and the similarities they share.

For my experience, the senses can be made perceived in the mode of the other specificity because even if they are traveling through different canal, they are link to one another. They work for one another and they are far more one living under separate aspect than divided tools of perception.

Tuesday, October 21, 2008

Father Time: The Liar

Deleuze takes up what Nietzsche begins in his own sober way. Narration is often deemed the truthful retelling of a story ‘as it was’, or, in terms of fictitious narration, the telling of a story in such a manner that the mode of telling gives the impression that it ‘could be true’ – the minimum conditions for truth are fulfilled – chronology, non-contradiction, etc. Deleuze, however, picks up on methods of narration that “[falsify] narration…[which] frees itself from this system [of judgment]; it shatters the system of judgment because the power of the false…affects the investigator and the witness as much as the person presumed guilty,” (133). Narration is no longer about passing judgment about what it true (i.e. who is guilty of non-conformity), but rather can tap into the creative, artistic power of the false, and its intimate relationship with “irreducible multiplicity,” (ibid). The power of the false is to allow for incompossible worlds and, in so doing, to display a direct image of time. Time in its directness, says Deleuze, is exactly what disallows truth – what today may be a battle tomorrow, tomorrow will indeed be no battle and the once-possibility of that battle becomes a lie (see 130). Time makes liars of us all.

Sunday, October 19, 2008

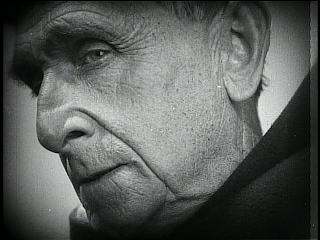

The Passion and the Affection

I know we are way past the affection-image in our readings, but after watching the Carl Th. Dreyer's The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928), I couldn't help but be reminded of those readings. It helps, that perhaps, the idea of the affection image has impressed itself on me in a greater way than many of Deleuze's other concepts.

Wednesday, October 15, 2008

Analogies of the crystal-image

The time-image is non-linear as it relates to both the virtual and the actual. We spend too much time focusing on the present, as it entails only a fraction of the future and the past combined.

The present is at its most interesting when its potential to the future is in a flux, or just before the virtual has manifested itself in the actual.

In some respects, Synchronicity refers to why one potential of the virtual is actualized over another. The dynamic of time is not just an unfolding (linear), but an expansion as well.

What is expanding? I tried to explain this in my last class with Erin in a gift of writing to another student. And here in this class, we encounter the crystal-image and my immediate reaction to this is the model of a hologram, where every piece contains an image of the whole.

A space-structure that defies linear thinking, or that even undermines it, because the crystal-image (or the Hologram) contain both the virtual and the actual simutaneously.

This is where the fusion between the two takes place. Linear time as we know it is suspended (within the crystal-image or Hologram) and thus change can occur.

Physicist Michio Kaku (http://mkaku.org/) in his book Hyperspace, imagines how the 4th dimension would appear to us if we were thrust into it: All would appear as blobs of form/ light floating around us, perhaps passing through us, without definition. Our faculties are simply not designed to perceive in such a space. Kaku uses the analogy of pulling a carp from water, for a fish cannot perceive our three-dimensional world, and would probably see blobs of form/ light floating around it, perhaps appearing to pass through it, without definition.

Tuesday, October 14, 2008

Sight for Sore Ears?

With hindsight I guess what I was trying to ask was, "If the visuals are super tight with the music, when you turn off the music does the eye respond to the visuals the same way that the ear responds to sound? Can sight acquire the sensorial specificity of hearing when the visual stimuli requires it to do so? Do we see differently when we ask sight to perform the task of hearing visually?" The question comes from reading Bergson's Matter & Memory p. 50 "[As per Lotze,] 'sound waves which should give to the eye the sensation of light or luminous vibrations which should give to the ear a sound.' The truth is that all the facts alleged can be brought back to a single type: the one stymulus capable of inducing the same sensation, are either an electric current or a mechanical cause capable of determining in the organ a modification of electrical equilibrium." I kinda feel that the aural circuit is different, from the visual circuit, or the olfactory circuit... but can they be made to "perceive" in the mode of the other 's specificity?

Another thing that didn't come up (but should've) in reading B. was the translated term "sensitive nerve" in Deleuze is nowhere to be found (up to the end of Chap.1), what did come up was sensorial nerve. I don't have the French Cinema 1 & 2 so I've never checked it... Does D. say nerf sensible?

Monday, October 13, 2008

Tarkovski, l’image-caractère et l’animation

Saturday, October 11, 2008

La Zone du temps

Cette connexion entre les trois temporalités se distingue particulièrement dans la scène de la traversée du tunnel dans la Zone. Les personnages progressent lentement dans l’espoir de parvenir au bout du tunnel, toujours dans la peur de mourir, dans le soulagement d’être parvenu jusqu’à ce point et dans l’angoisse de n’être en mesure de se rendre jusqu’à bout. La limite du tunnel leur permet d’envisager une fin heureuse, mais le point où ils se trouvent à l’instant les maintient dans un état de frayeur constant. Ils sont dans le présent, tout en étant tiraillés entre le passé et l’avenir.

Friday, October 10, 2008

look at this

See for you self at this address: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MPJJSCFdVd0

la Zone, ou le lieu que décrit Deleuze

Thursday, October 9, 2008

The vernacular and the visceral

Both hark back to a certain cultural rawness (of language, of interior being ).

Aesthetics have a relationship to these words when we see something that is not following particular or predictable patterns. We are drawn into the nuances of a visual language that may be only coming into being, and that birth has its origin in these two words. Doesn't everything?

(re)voir

Interacting with McLaren

La Jetée... some scattered thoughts

watching again...and again

Également: comment lire entre les lignes?! En devenant étudiant en Film Studies, bien sûr. Combien de fois prêtons-nous des intentions au réalisateur qui était à cent lieues d'avoir imaginé une scène telle que nous la percevions? La perception au cinéma, la perception et le cinéma, semblent être des sujets primordiaux, certes, mais relatifs à chacun. Le post de Janita en rend merveilleusement compte.

VENOM & ETERNITY (Traité de bave et d'éternité)

Jean-Isadore Isou sought to revolutionize art and cinema.

Jean-Isadore Isou sought to revolutionize art and cinema.Part of this revolution had to do with how sound was used to disrupt the moving image.

Or from another perspective, how the concepts of the Lettrist Movement, translated to film, disrupted the secure notions of the viewer as being outside the film.

During the third sequence of this film, titled, The Proof, angry male voices become a dissonant background. This underlying vocal layer, like an unseen canvas of chaotic sound, becomes a moving unseen image, behind the cinematic.

Can this purposeful use of disturbing, chaotic sound be seen in itself as an unseen image.

Isou writes: In this work, I was more excited about the schism of image than about satisfying the demands of convention."

This schism of image is perhaps an early attempt to see between the frames , where four trajectories: art, philosophy, cinema, and sound crash in the viewer's subconscious.

Watch: Eternity and Venom 2hrs

Wednesday, October 8, 2008

watching again

I’m still thinking about the object also being an image, a perception, and how this relates to repetition. Ever since I was young I have liked most of all to watch movies that I have already seen. Negotiating the world around the images is such a task and still leaves so much out, that the same movie can be seen again and again, and each time it is something slightly different than what it was before. Maybe this is appealing because watching again allows for habits of perception to form so that new aspects of the encounter may be perceived. But have I ever actually watched the same movie twice? Each time a film is encountered it is in concert with a new constellation of events, and the film I see is only one film of many, subtracted out of the whole of the film through my subjective perception. Watching a film again is not proof that a pre-constituted film exists and is now being presented to me again, but rather that the remembered version of the film is activated by the second showing and through this memory the present film becomes as a new relation. My impulse to watch a movie I have already seen is in fact a desire to revisit a becoming-with the present moment which is activated by residues of the past.

Tuesday, October 7, 2008

Animating Up and Down the Street.

And it is in this awkward and tentative becoming that something extraordinary happens that Erin calls moving the relation. As soon as you move the relation, you engage the micropolitical. It’s an interesting way of thinking about what constitutes the political and how to participate in the political process by incorporating its aesthetics. These ideas surround principles of heightened subjectivity, relation and process. For me, what I’ve taken out of it is and what I’m sure is a cliché for you all, is that you can make a difference by participating in any activity, in any process. However, the way that I understand their process of participation is by fomenting subjectivity. It’s not a question of a right approach or the right direction, but one of embarking on a process, any process and letting it develop, mutate, unfold, change you.

The idea is to make things happen, to celebrate becomings, to inflect anything that moves with your subjectivity, personality, character or whatever you want to call it. We all do this more or less as a matter of course on a daily basis; most likely the people you interact with on a regular basis would likely miss you if you suddenly went missing. But I think that what constitutes the micropolitical difference is to make a conscious effort to inflect some activity in your life with a gesture that will generate animation, movement to subjectivity. To give it spin. We hear the word spin all the time applied to sports and obviously to politics. But the kind of spin I’m talking about is a lot smaller than that. It consists of dropping a seed, a nugget of possibility, a germ of potential and to let it grow, let it germinate. It’s not a question of doing the grand-geste afin d’épatter les bourgeois. The micropolitical activist is a political Johny Appleseed, or if you prefer un Homme qui plantait des arbres—like the character in Frederic Bach’s animated film. You plant the seed and walk on to plant others. It doesn’t matter where the seed falls, or whether it germinates, or becomes a huge tree. What matters is the process and not the outcome; you’ve changed in some minor and perhaps imperceptible way the unfolding of the universe of potential. You break a strand in what would have been the inevitable becoming of a future becoming past and spin the future into a something ever so slightly different that is tinged with more of your subjectivity. The key is not to get ego-involved with the seeding: don’t look back, move on to the next animation, to the next movement relation.

If you don’t like what's going on, make signs on 8 ½ x 11 paper right out of your computer with what you want to say and put it up on bulletin boards and telephone poles in your neighbourhood. Make copies and stuff them in people’s mail boxes on your street. Do it without asking anyone or telling anyone, just do it. Just thinking about this should make you feel awkward and stupid. Simply acknowledge that it is creativity and your self-becoming. Your $6 campaign will result in change, perhaps ever so slightly and imperceptibly. Any kind of small change to the intuition of the future is a micropolitical move of the relation. Who knows what it will bring, who cares? Move on!

The Stuff of Time

I also watched Chris Marker's La Jetée recently, and while I was reading the text for this week, I was struck by some passages that could be read fruitfully with aspects of the movie. A man who has survived the 3rd World War is asked by his captors to allow them to conduct experiments on him. Since humanity is doomed, he agrees. Space has been made off-limits through radioactivity, and so there is only time through which humans may move. This man is asked to focus on an image from his childhood in order to experiment with the movement through time. After he succeeds in moving through time to the past, he then attempts to move through to the future.

I won't tell you anything more about the photo-novel, in case you haven't seen it. But the thought experiment gave me ways to sense what is at stake when Deleuze (with the help of Bergson) links movement to time in terms of memory. When it is no longer possible to subscribe to the illusion that we move through space (like when we are stuck underground because of radioactivity) we perhaps become aware of the movement of (in!) time and that it is not linear, that is, it is not chronological. It is not we as subjects who "feel" time pass, but rather "the only subjectivity is time, non-chronological time grasped in its foundation, and it is we who are internal to time," (82). Memory is no longer considered as the constitutive moment of a person or subject (ie. you are what you remember), but rather it is the world of experience through which everything moves - rephrased again: it is not a subject that remembers (no Weltgeist here!) but rather memory is the matter of the world. Hence Bergson's book title: Matière et Mémoire?

Sunday, October 5, 2008

Movement as Language by Len Lye

Friday, October 3, 2008

Image-son, Lipsett et Hébert

Steve offre une formulation intéressante de l'image-son, de l'articulation entre l'image et le son à l'écran en soulignant que «l'image possède la force de s'approprier le son.» Les films de Lipsett, entre autres, nous forcent en effet à questionner l'image-son et sa capacité à créer des évènements qui ne sont plus ni uniquement visuels ni uniquement sonores mais audiovisuels. J'ai fait l'exercice de regarder Very Nice Very Nice (1961) de Lipsett une première fois avec le son et une seconde fois en coupant le son. La bande sonore pourtant hétéroclite (dans la même veine que celle de Free Fall et A Trip Down Memory Lane que nous avons vu en classe) semble vraiment avoir cet effet que mentionne Steve de donner du mouvement aux images fixes, d'intersecter avec les images et de créer des évènements audiovisuels où l'on ne peut plus distinguer l'effet spécifique du son de celui de l'image. Les films de Lipsett gardent néanmoins un grand potentiel de déstabilisation. Les évènements audiovisuels auxquels ils nous confrontent ne sont pas intégrés à un déroulement unifié ou à un flot continu de mouvement mais se forment, se déforment et se reforment de façon plus ou moins imprévisible.

Le second visionnage de Very Nice Very Nice, sans le son, m'a évidemment permis de porter une attention accrue à certains détails et qualités de l'image. Le mouvement semblait ici provenir de la différence, de l'écart, entre la texture et le grain des images, et non plus du rythme 'imposé' par la bande sonore. Ce mouvement subtil me semble être proche de «l'imperturbable» que Pierre Hébert considère, au début de son essai «Éloge de la fixité», comme la perte (presque) inévitable et inverse résultant de l'ajout du mouvement au dessin fixe. Si les techniques de prédilection respectives de Lipsett et Hébert ont peu à voir les unes avec les autres, j'ai toutefois l'impression que l'on peut rapporter leur démarche à cette possibilité, évoquée par Hébert, «d'animer l'imperturbable» en essayant d'échapper à l'empire de l'indubitable et à l'hégémonie du mouvement sur l'image (p. 17). Sans le son, les images de Very Nice Very Nice m'ont permis de voir comment le mouvement pouvait être retenu tout en se déployant. Cela étant dit, je ne veux pas insinué que la bande sonore gâche cet effet ou range le film dans le domaine de l'indubitable. L'image-son et ses différentes articulations me semblent cependant, à ce stade-ci, encore trop complexes pour être capable de cerner l'effet de la bande sonore sur cette sensation «d'imperturbable».

Thursday, October 2, 2008

Une Variété de perceptions

La perception d’une œuvre d’art ne varie pas seulement d’un individu à l’autre, mais aussi selon notre propre expérience. En écoutant le documentaire sur Norman McLaren, je suis parvenue à avoir une toute nouvelle vision d’un film que je connaissais pourtant très bien. Jusqu’à aujourd’hui, le mouvement des formes dans Mosaïque était pour moi un agencement de carrés se rapprochant et se repoussant continuellement. Pourtant, après avoir écouté McLaren expliquer qu’il s’agissait de points entre les intersections de lignes verticales et horizontales, le film semble désormais prendre à mes yeux une forme nouvelle. Ce ne sont plus les points qui s’animent, mais plutôt les lignes invisibles que je perçois. Ce qui est fascinant avec une œuvre d’art aussi captivante, c’est qu’il semblerait possible de la regarder indéfiniment et en comprendre une signification nouvelle et plus profonde à chaque fois. J'en déduis aussi que notre perception naturelle se renouvelle selon l'évolution de notre mode de pensée.

Reawakening Perception

Analogy and utterance

In Deluzian terms the structure underlying these utterances is clearly an analogy and the

"... digitized structure of the utterance...But the very point the image is replaced by an utterance, the image is given a false appearance and...movement is taken away from it."

Erin: I see the associations Deleuze is making here. Could you comment in relation to this animation?

Please watch:

http://www.waliczky.com/pages/Wallada-Bioscop/Marionettes/Marionettes.htm

Wednesday, October 1, 2008

(Past) Present (Future)

“It is characteristic of cinema to seize this past and this future that coexist with the present image” (Deleuze, 37)